The Plague Doctor: navigating disease historically and today

Rumours of deadly disease spread from Asia faster than the disease itself. When a trade ship turned up in Sicily with its crew either dead or about to follow, it was clear the disease had finally hit Europe. Families were left with the devastating choice to either die with an afflicted loved one of leave them alone to save themselves. The clothes, possessions and whole houses of the departed may have been burnt in an attempt to contain the plague.

Various strategies were implemented to stop the spread and to understand its cause. Universities emplyed astrologers to chart the star and planet formations responsible. Religious figures grapped with their interpretation of God's intention. But one thing missing from the scene was the beak-masked Plague Doctor - because the costume was not invented for another 250 years.

The Plague Doctor’s Costume was conceived in the 1630s. Its inventor is often credited as French doctor Charles de Lorme. The idea was that the body was protected from contagious contact, the stick could evaluate a patient from a distance, and the beak would store herbs that would cleanse dangerous bad smells that were the core of the miasma theory of disease.

But back in the 1340s, miasma theory was much less developed. Instead, they might have tried bloodletting to balance the four humours, according to Roman physician Galen’s millennia old theory. But as up to sixty percent of the population died, scapegoating was used in place of an explanation. It was God’s punishment of the sinners of the world. It was the Jews poisoning Christians. It was all because of the cats.

Thankfully, we haven’t seen a case of the plague on the same scale since. There have been many small outbreaks across many cities, like in London in 1592, 1620 and 1665. This is when we see the plague doctors, who were people contracted by cities specifically to treat plague victims. Citizens may even have given them provisions to help them with their work. However, despite the job title, it is uncertain these doctors wore the infamous costume. Just because Charles de Lorme might have proposed the outfit and outlined its protective benefits does not mean it was in widespread use across the seventeenth century.

Genevan physician Jean-Jacques Manget’s Traite de la Peste outlines contemporary knowledge of the plague and details various remedies. The frontpiece is an engraving of the plague doctor costume that the text dates to an outbreak in the Netherlands in 1637. Manget’s book was published in 1721, nearly a century after the outbreak this costume was reportedly in use. The year 1721 is important. It was the year of the Great Plague of Marseille, the last major outbreak of the plague in Western Europe. Publications from around that time remembered previous outbreaks, how deadly they were and how they were dealt with. A Treatise of Pestilence by an ‘Eminent Physician’ considered the 1665 London outbreak. Another 1721 text republished texts relating to previous plagues, like the Mayor of London’s instructions to citizens in 1665, a mortality report of various English outbreaks since 1592, and an account of the 1656 outbreak in Italy. They were using past instances of the plague to help them comprehend and navigate the current plague.

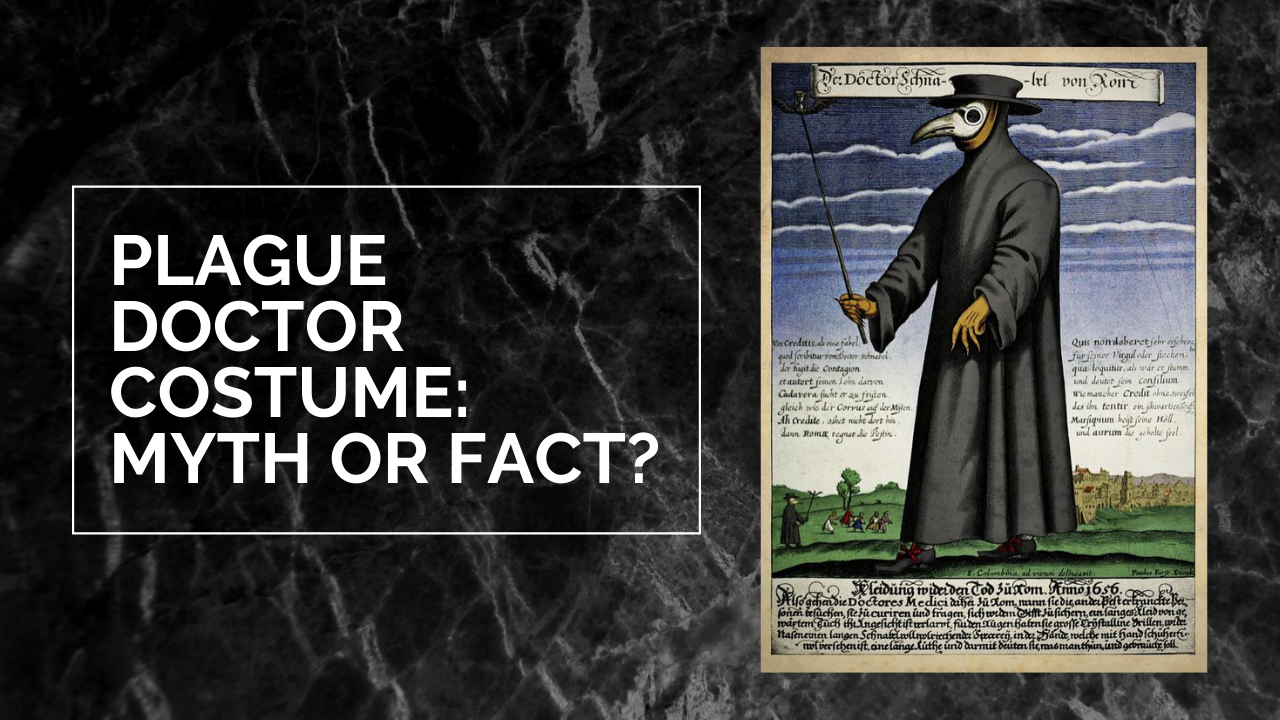

In contrast, seventeenth-century sources satirise the Plague Doctor Costume instead of legitimising it as standard apparel. A 1650s wood engraving by Paulus Fürst shows a Plague Doctor in full attire. The title translates as ‘Doctor Beak of Rome’. The doctor’s stick features an hourglass and bat wings, which can only be there as a comic element rather than any practical purpose. In the corner, a plague doctor brandishes his stick towards some people who are fleeing, presumably to the plague-stricken town. The Plague Doctor Costume may have been used in Italy during the 1650s, but when word of the outfit travelled further west, people thought it was absurd. Notice this is a German source commenting on Italian plague practices – they might not have seen the outfit themselves.

The prevalence of the Plague Doctor image means it isn't so much about the history but the feelings we want to convey when we use it. Just like people during the 1720 plague outbreak, we’re thinking about past instances of illness to help us process our current situation. The Plague Doctor has entered the visual iconography of how people understand historical disease. The Venice Carnival traditionally has a procession of people wearing a bastardised version of the plague doctor mask. We can buy Halloween costumes of the outfit in the same way we might dress up as a skeleton or a zombie, commodyfying a sense of rustic unease. It symbolises a world without modern medicine or understanding of disease. It’s how we think about a world without antibiotics and without sanitisation and when the best known cures were some mecidinal herbs and, if all else, fails, tying a pigeon to their buboes.

Bibliography

Primary sources

AFP News Agency, 'Venice carnival: Procession featuring 'plague doctor' masks | AFP', Feb 25 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SMO-GyZ4lWs

Anonymous, A treatise of the pestilence: with its Pre-Vision, Pro-Vision and Prevention, and the Doctor's Method of Cure (London: 1721)

Anonymous, A collection of very valuable and scarce pieces relating to the last plague in the year 1665 (London: 1721)

Jean-Jacques Manget’s, Traite de la Peste (Geneva: 1721)

Paul Fürst, 'Der Doctor Schnabel von Rom', copper engraving, Germany, 1656

The orders and directions, of the right honourable the Lord Mayor and Court of Aldermen, to be diligently observed and kept by the citizens of London, during the time of the present visitation of the plague (London: 1665)

Secondary Sources

Christian J. Mussa, 'The Plague Doctor in Venice', Internal Medicine Journal, 49 (2019)

Frank M. Snowden, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present (Yale: Yale University Press, 2019)

G.L.T, 'The Plague Doctor: An engraving by Gerhart Altzenbach (17th century)', Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 20, No. 3 (1965)

M. Rambaran-Olm, '“Black Death” Matters: A Modern Take on a Medieval Pandemic', Medium, 2019 https://medium.com/@mrambaranolm/black-death-matters-a-modern-take-on-a-medieval-pandemic-8b1cf4062d9e